In one part of an article that I recently published, I discussed the interim Cass Report. I linked to the full report document itself and then summarised the findings. Dr Hilary Cass has been conducting an independent review of the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) in the UK, and my summary of her interim report included screenshots of the changes that she had recommended to GIDS. Nevertheless, there have since been allegations that I have seriously misunderstood or misrepresented the report.

My summary of the findings from the Cass Report, was that GIDS had no agreed criteria on which to determine whether any gender dysphoric child was transgender or otherwise. This was clearly a serious problem since the treatment pathway prescribed in such a circumstance was life-altering, with the puberty blockers alone often resulting in sterilisation. I went on to state that for these reasons, the National Health Service (NHS) in England decided to close down GIDS entirely and replace it with a new service. Based on the serious concerns described in the Cass Report, the two new NHS clinics that replaced GIDS would be explicitly prohibited from prescribing puberty blockers outside of a clinical research setting.

In contrast, it was suggested that the true findings of the Cass Report were that GIDS had merely been overwhelmed by the number cases, such that it was unable to prescribe puberty blockers to enough children. Consequently, there was an insistence that the two new NHS clinics were being opened in order that puberty blockers would be prescribed to even more children.

Clearly these two interpretations of the same document are poles apart. As such, I have provided a few quotes from the document itself below, which I hope will bring some clarity to the issue. Against that, I recommend reading the entire report itself. The full report can be read in under an hour. There were a few terms that I had to look up (I learned that “aetiology” refers the cause of any given medical condition) but in general it is a very accessible document.

Uncertainty About The Condition

When gender dysphoric children presented at GIDS, the clinicians within the service could not agree on the nature of this condition. In describing the context for her review, Dr Cass stated as follows in paragraphs 2.15 and 2.18 of her report (on page 28):

“… there are widely divergent and, in some instances, quite polarised views among service users, parents, clinical staff and the wider public about how gender incongruence and gender-related distress in children and young people should be interpreted … The disagreement and polarisation is heightened when potentially irreversible treatments are given to children and young people, when the evidence base underlying the treatments is inconclusive, and when there is uncertainty about whether, for any particular child or young person, medical intervention is the best way of resolving gender-related distress.”

Quotes from the Cass Report

After listening to the clinicians at GIDS, Dr Cass included some more detail in paragraph 4.15 of her report (on page 47) about just how much clinical uncertainty there was in relation to gender dysphoria:

“Clinicians and associated professionals we have spoken to have highlighted the lack of an agreed consensus on the different possible implications of gender-related distress – whether it may be an indication that the child or young person is likely to grow up to be a transgender adult and would benefit from physical intervention, or whether it may be a manifestation of other causes of distress. Following directly from this is a spectrum of opinion about the correct clinical approach, ranging broadly between those who take a more gender-affirmative approach to those who take a more cautious, developmentally-informed approach.”

Quote from the Cass Report

Dr Cass then goes on to discuss the principles that should underpin the development of the new replacement service that she would recommend instead of GIDS. In paragraph 5.8 of her report (on page 58) she reiterates that there is no clinical or academic agreement on the nature of the condition that gender dysphoric kids will present with:

“Regardless of aetiology, the more contentious and important question is how fixed or fluid gender incongruence is at different ages and stages of development, and whether, regardless of aetiology, it can be an inherent characteristic of the individual concerned. There is a spectrum of academic, clinical and societal opinion on this. At one end are those who believe that gender identity can fluctuate over time and be highly mutable and that, because gender incongruence or gender-related distress may be a response to many psychosocial factors, identity may sometimes change or the distress may resolve in later adolescence or early adulthood, even in those whose early incongruence or distress was quite marked. At the other end are those who believe that gender incongruence or dysphoria in childhood or adolescence is generally a clear indicator of that child or young person being transgender and question the methodology of some of the desistance studies.”

Quote from the Cass Report

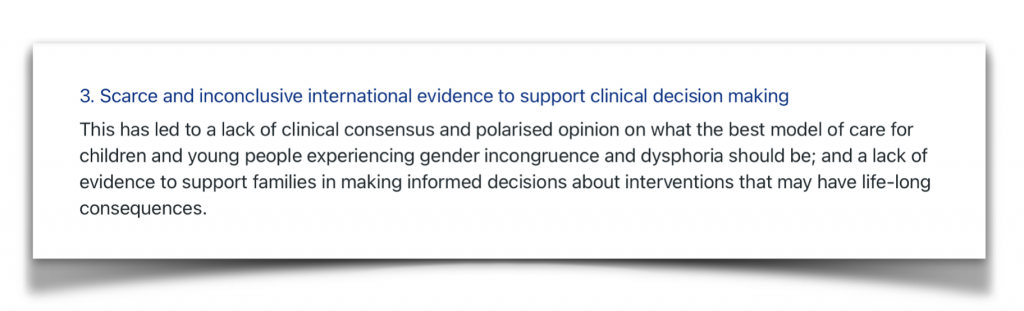

Given that there is no agreement among clinicians in the UK or anywhere else about what the nature of childhood gender dysphoria actually is, perhaps it is not surprising that there is no agreement about the most appropriate treatment either.

Uncertainty About The Treatment

The NHS set up a Multi Professional Review Group (MPRG) to ensure that appropriate procedures for assessment and informed consent are followed, which is an important safeguard for vulnerable children when life-altering treatments are a possibility. In paragraphs 1.18 and 3.48 of her report (on pages 17 and 43) Dr Cass describes how the MPRG viewed the assessment of treatments for gender dysphoric children at GIDS:

“From documentation provided to the MPRG, there does not appear to be a standardised approach to assessment or progression through the process, which leads to potential gaps in necessary evidence and a lack of clarity … The MPRG indicates that there does not appear to be a standardised approach to assessment. They are particularly concerned about safeguarding shortfalls within the assessment process.”

Quotes from the Cass Report

Any conscientious parent would be terrified to hear that the professionals in the field are “particularly concerned about safeguarding shortfalls” when it comes to prescribing life-altering treatments to their children. In paragraphs 1.23 and 4.18 (on pages 18 and 48) of her report, Dr Cass went on to describe the very substantial disagreements among GIDS clinicians and other professionals around the world, about what treatments should be prescribed for a given set of symptoms and circumstances:

“Evidence on the appropriate management of children and young people with gender incongruence and dysphoria is inconclusive both nationally and internationally … GIDS staff have confirmed that judgements are very individual, with some clinicians taking a more gender-affirmative approach and others emphasising the need for caution and for careful exploration of broader issues. The Review has been told that there is considerable variation in the approach taken between the London, Leeds and Bristol teams.”

Quote from Cass Report

In the ‘Findings’ section of her report, Dr Cass mentions in paragraph 4.36 (on page 51) the rather obvious conclusion that there is a need for a “robust evidence base” to support the prescription of “different pathway options”. At GIDS, extremely consequential treatment pathways were being prescribed in the absence of this very necessary evidence.

“Concerns were expressed by professionals who took part in this research about the lack of consensus among the clinical community on the right clinical approach to take when working with a gender-questioning child or young person and their families/carers. In order to support clinicians and professionals more widely, participants felt there is a need for a robust evidence base, consistent legal framework and clinical guidelines, a stronger assessment process and different pathway options that holistically meet the needs of each gender-questioning child or young person and their families/carers”

Quote from the Cass Report

That is, the reason why there were such widely divergent views among the clinicians at GIDS with respect to different treatment options, is that there is no good evidence to support the efficacy of one treatment pathway versus another. None of the clinicians at GIDS, who had very different views about the use of puberty blockers, had any good evidence to support their intuitions. The implications of this have been reported in detail by Hannah Barnes, a BBC journalist who has interviewed very many patients and clinicians at GIDS:

The safeguarding risk that arose from the uncertainties at GIDS, related to prescribing life-altering drugs to “false positive” cases. That is, children who would otherwise have observed their gender dysphoria desist naturally during a normal puberty, were instead given very consequential drugs. The term “false positive” is a euphemism for the entirely unnecessary chemical sterilisation of vulnerable and distressed children.

Uncertainty About Patient Demographics

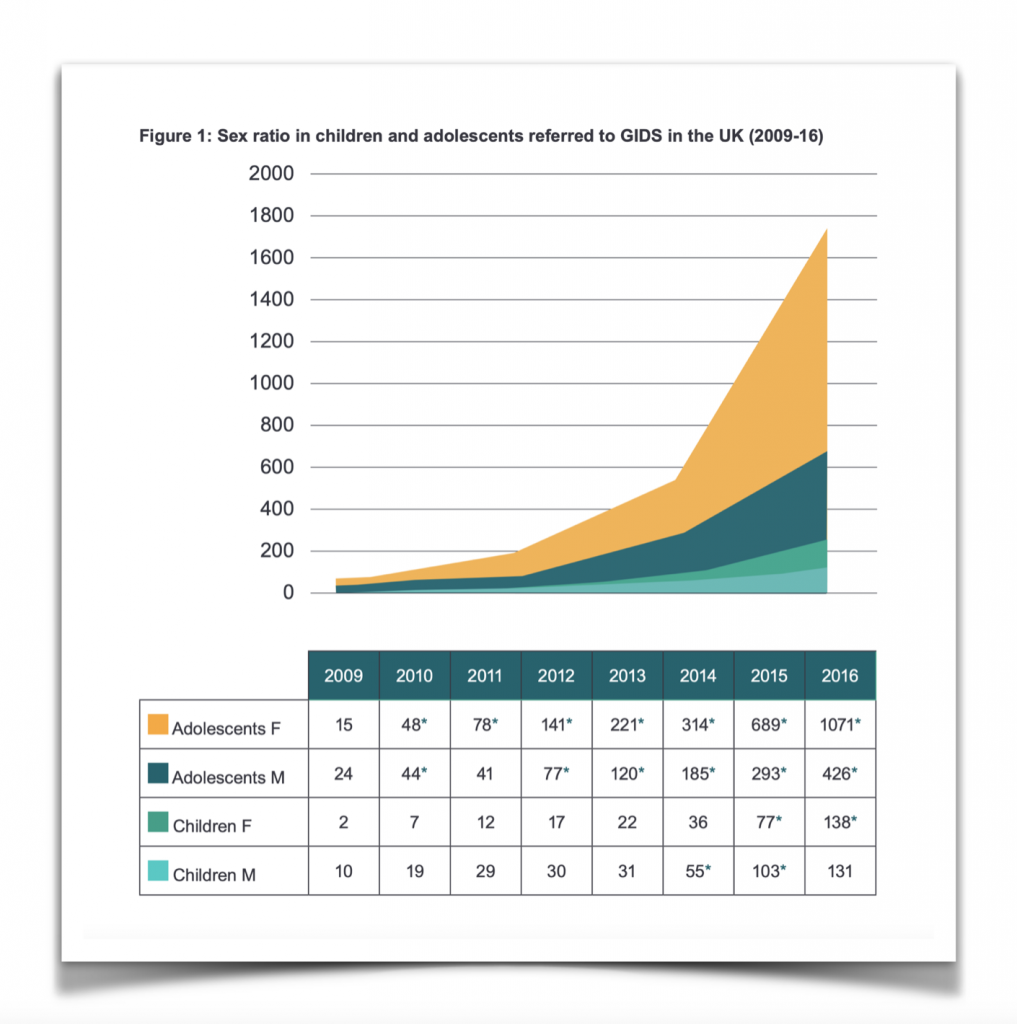

Another issue that caused Dr Cass some concern, was the enormous unexplained increase in GIDS cases that were coming from specific demographics. Over a small number of years, a huge number of girls began presenting at GIDS. Whereas in 2009 there were twice as many boys as girls, by 2016 there were more than twice as many girls as boys.

In addition to the longer waiting times implied by a rapidly increasing caseload, of even more concern was the unexplained increase in the incidence of autism among GIDS patients. The original research that GIDS was based on had been carried out in The Netherlands, and those studies had explicitly excluded patients with autism or other mental disorders. The motivation for this was to exclude the possibility that any gender dysphoria was being caused by mental health comorbidities, rather than because a transgender child had been “born in the wrong body”. In paragraphs 1.20 and 3.6 of her report (on pages 18 and 31) Dr Cass described how the GIDS approach at the NHS subsequently diverged from “the Dutch Approach”:

“The Netherlands was the first country to provide early endocrine interventions (now known internationally as the Dutch Approach). Although GIDS initially reported its approach to early endocrine intervention as being based on the Dutch Approach, there are significant differences in the NHS approach. Within the Dutch Approach, children and young people with neurodiversity and/or complex mental health problems are routinely given therapeutic support in advance of, or when considered appropriate, instead of early hormone intervention … the Dutch Criteria for treating children with early puberty blockers were: (i) a presence of gender dysphoria from early childhood; (ii) an increase of the gender dysphoria after the first pubertal changes; (iii) an absence of psychiatric comorbidity that interferes with the diagnostic work-up or treatment …“

Quotes from the Cass Report

The research on which the GIDS clinicians were basing their treatments and prescriptions, had explicitly excluded patients with autism or other mental disorders from participating. As such, the original Dutch research is silent on the treatment of gender dysphoric kids who have mental health comorbidities. However, fully one third of all the children being treated by GIDS fell into this category. Dr Cass described this change to the patient demographics in paragraph 3.11 of her report (on page 32):

“This increase in referrals has been accompanied by a change in the case-mix from predominantly birth-registered males presenting with gender incongruence from an early age, to predominantly birth-registered females presenting with later onset of reported gender incongruence in early teen years. In addition, approximately one third of children and young people referred to GIDS have autism or other types of neurodiversity.”

Quote from Cass Report

The GIDS clinicians had absolutely no evidence on which to base their treatment of autistic patients, and they had no idea why the demographics of their patients had shifted so much and so quickly. Since it seemed unlikely that the incidence of transgender children had spontaneous shifted from very young boys to autistic teenage girls, the potential for more “false positive” cases was then especially high. That is, the sharp rise in caseload argued for increased caution when prescribing pharmaceutical interventions.

Uncertainty About The Outcomes

Even after life-altering treatments had been prescribed to gender dysphoric children, the clinicians at GIDS did not know whether those treatments had worked or not. There is no good international evidence in this area either. In paragraph 3.21 of her report (on page 36) Dr Cass states as follows:

“The most difficult question in relation to feminising/masculinising hormones therefore is not about long-term physical risk which is tangible and easier to understand. Rather, given the irreversible nature of many of the changes, the greatest difficulty centres on the decision to proceed to physical transition; this relies on the effectiveness of the assessment, support and counselling processes, and ultimately the shared decision making between clinicians and patients. Decisions need to be informed by long-term data on the range of outcomes, from satisfaction with transition, through a range of positive and negative mental health outcomes, through to regret and/or a decision to detransition. The NICE evidence review demonstrates the poor quality of these data, both nationally and internationally.”

Quote from Cass Report

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) had been commissioned to review all of the international evidence on the efficacy of cross-sex hormone treatments for gender dysphoric children. They also reported considerable uncertainty about the efficacy of puberty blockers. In paragraphs 3.24 and 3.31 of her report (on pages 37 and 38) Dr Cass stated as follows:

“The administration of puberty blockers is arguably more controversial than administration of the feminising/masculinising hormones, because there are more uncertainties associated with their use … The most difficult question is whether puberty blockers do indeed provide valuable time for children and young people to consider their options, or whether they effectively ‘lock in’ children and young people to a treatment pathway which culminates in progression to feminising/masculinising hormones by impeding the usual process of sexual orientation and gender identity development. Data from both The Netherlands and the study conducted by GIDS demonstrated that almost all children and young people who are put on puberty blockers go on to sex hormone treatment (96.5% and 98% respectively). The reasons for this need to be better understood.”

Quotes from the Cass Report

When the clinicians at GIDS prescribed puberty blockers to young children, they were invariably placing those kids onto a life-altering and irreversible treatment pathway. They had no good evidence indicating whether the outcomes of such very consequential treatments were positive or negative.

The Response Of The NHS

The Cass Report describes a set of clinicians at GIDS who couldn’t agree about the condition they were treating; couldn’t agree about which treatments should be prescribed for any given patient; couldn’t understand why the demographics of their patients were changing so quickly; and didn’t have any good evidence for whether the life-altering treatments they were prescribing were having a positive or negative outcome. In fact, the most recent evidence (from an admittedly small study) is that after 12 months of puberty blocker injections; 34% of the children had reliably deteriorated; 29% had reliably improved; and 37% showed no change.

On the basis of the interim Cass Report, the NHS decided to close down GIDS and create two new clinics to take over the management of the paediatric gender dysphoria caseload in the UK. These two new clinics would be explicitly prohibited from prescribing puberty blockers outside of clinical research. This NHS announcement stated as follows about the conclusions within the interim Cass Report:

The NHS announcement went on to state as follows with respect to the changes that they would implement based on the Cass Report:

“Phase 1 service providers (previously referred to as Early Adopter Services), will take over clinical responsibility for seeing children and young people on the national waiting list as well as providing continuity of care for the GIDS open caseload at the point of transfer. The Tavistock GIDS service itself will be decommissioned as part of a managed transition of the service to the new Phase 1 service providers … the NHS will only commission puberty supressing hormones as part of clinical research. This approach follows advice from Dr Hilary Cass’ Independent Review highlighting the significant uncertainties surrounding the use of hormone treatments. We are now going out to targeted stakeholder testing on an interim clinical commissioning policy proposing that, outside of a research setting, puberty suppressing hormones should not be routinely commissioned for children and adolescents who have gender incongruence/dysphoria.”

Quote from NHS announcement following publication of the Cass Report

Based on the findings described in the Cass Report, GIDS was closed down. The two new clinics that would take over the GIDS caseload were explicitly prohibited from prescribing puberty blockers outside of a clinical research setting. That is, the treatment pathway that GIDS had placed thousands of children onto, would no longer be followed by new patients.

Conclusion

In contrast to the above, some people recently claimed to have read the Cass Report and understood the central finding to be that too few children are being prescribed puberty blockers. Their suggestion is that the key problem identified in the report is excessive waiting times, such that two new clinics are being opened by the NHS in order to prescribe more puberty blockers, more quickly, to more children. Perhaps it is not a coincidence that these are the same people who think that the entirely unnecessary sterilisation of vulnerable and distressed children is “not the end of the world”. In the video clip at the top of this page, it is stated that the Cass Report arrived at the following conclusions:

“[The GIDS closure] is not because they were giving them drugs they shouldn’t have been given. It’s because they weren’t getting access to the drugs they needed … It wasn’t about prescribing stuff that wasn’t supposed to be prescribed, or prescribing it wrong … [the problem was that] they were not giving medical care to trans people. That’s why there was a problem … [trans people] were not getting prescribed the required drugs … [The Cass Report] was about people not getting prescribed drugs when they were needed because of long waiting lists … That’s why they split the clinic in two to spread the load.”

An alternative interpretation of the Cass Report

These are not good-faith statements about an important document, which seeks to ensure the best possible care for gender dysphoric kids. This is mere ideological point-scoring, irrespective of the harm that is being caused to vulnerable children in distress. The full videos distorting the Cass Report are here and here.

4 responses to “What Does The Interim Cass Report Actually Say?”

[…] months ago I wrote an article about the interim Cass Report, in which I summarised the findings with detailed references to the document itself. Dr Hilary Cass […]

[…] the UK. The conclusions and recommendations in this final report are entirely consistent with those of her interim report, with a much more detailed review of the available scientific evidence now being provided. What she […]

[…] had also written another article about the conclusions of the Interim Cass Report, which mentioned that the NHS withdrew the routine prescription of puberty blockers as a result of […]

[…] clarity, my article on the interim Cass Report did not say that “puberty blockers are sterilising kids”. That article explicitly […]