There are many provisions across the Irish Statute Book that award certain benefits to the religious, which are unavailable to the non-religious. For example, there are tax benefits associated with funding “the advancement of religion”, while the promotion of humanist philosophies does not attract any such consideration. In order to allocate these benefits, the Irish State must then define what qualifies as a religion and what does not. Various public bodies in Ireland have made such distinctions in a number of different ways, some of which are summarised below. Full copies of all the related documents are available at the bottom of this page.

The Civil Registration Act

One Irish law that provides religious bodies with specific benefits, which are denied to secular bodies, is the Civil Registration Act. This law describes inter alia which groups and organisations that may conduct a marriage that will be recognised by the State. There are an onerous set of conditions that must be met by a secular body in order to be registered for this purpose, while the same set of conditions need not be met by the religious.

The Civil Registration Act defines a “religious body” as:

“an organised group of people members of which meet regularly for common religious worship”

Quote from the Civil Registration Act

I applied to the Civil Registration Service in order to register the Church Of The Flying Spaghetti Monster as a religious body in Ireland, describing how the members meet regularly for common religious worship. My application was rejected and according to Section 56 of the Act, I appealed this decision to the Minister. The Registrar General of Ireland made a written submission to this appeal process, and a full copy of that document is available at the bottom of this page. In summary, the core arguments offered by the Registrar General in rejecting my application, were that the content of my Pastafarian beliefs do not qualify as religious in nature, and that my atheism is not consistent with religiosity. I provided a detailed written response to the Registrar General as part of the appeal process. A full copy of my written submission is also available at the bottom of this page. For convenience the arguments contained within these documents are summarised below.

Content Of Beliefs

Whereas the primary legislation defines a religious body as a group of people who meet for “religious worship”, the Registrar General interpreted this language as requiring him to make a judgement about the “religious beliefs” of applicants. This is despite the fact that the Civil Registration Act does not refer to religious belief or its contents in any way. Moreover, even if the legislation did refer to religious belief, human rights law precludes the State from deciding which religious beliefs are legitimate and which are not. For example, the full European Court of Human Rights decision in Manoussakis v Greece is available at the bottom of this page and §47 includes the following statement:

“The right to freedom of religion as guaranteed under the Convention excludes any discretion on the part of the State to determine whether religious beliefs or the means used to express such beliefs are legitimate.”

Quote from Manoussakis v Greece

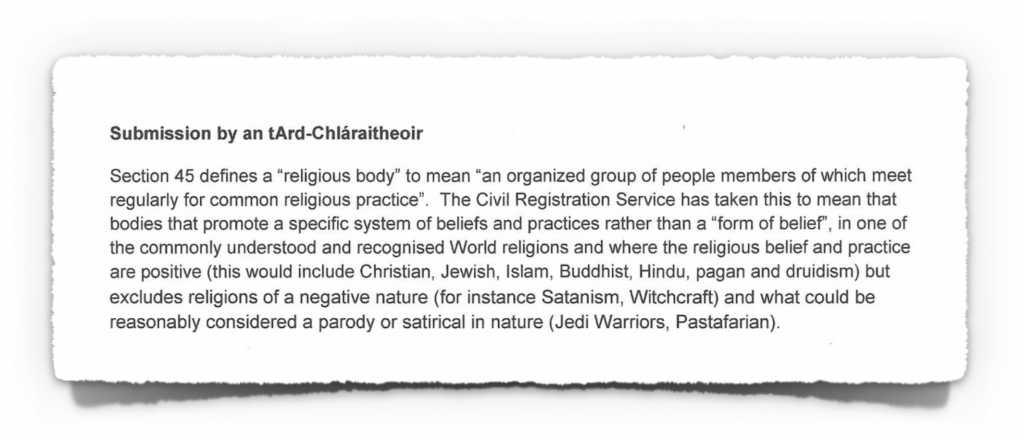

Notwithstanding this, the Registrar General of Ireland has decided to arrange various religious beliefs into positive and negative categories. This is based purely on subjective opinion and no criteria are used to determine which category various beliefs should belong to. Based only on these subjective judgements about which religious beliefs the Registrar General is well disposed to or otherwise, citizens are either awarded or refused the commensurate benefits from the Irish State. The relevant extract of the written submission from the Registrar General is illustrated below.

It is informative to contrast Catholicism with Satansim in this context. The Satanic Temple adheres to the romantic interpretation of Satan described by Shelly and Blake, as the hero of Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ who rebelled against tyranny. It teaches the following seven fundamental tenets:

- One should strive to act with compassion and empathy toward all creatures in accordance with reason.

- The struggle for justice is an ongoing and necessary pursuit that should prevail over laws and institutions.

- One’s body is inviolable, subject to one’s own will alone.

- The freedoms of others should be respected, including the freedom to offend. To wilfully and unjustly encroach upon the freedoms of another is to forgo one’s own.

- Beliefs should conform to one’s best scientific understanding of the world. One should take care never to distort scientific facts to fit one’s beliefs.

- People are fallible. If one makes a mistake, one should do one’s best to rectify it and resolve any harm that might have been caused.

- Every tenet is a guiding principle designed to inspire nobility in action and thought. The spirit of compassion, wisdom, and justice should always prevail over the written or spoken word.

The Irish State considers these beliefs to be negative. Consequently, members of The Satanic Temple may not enjoy those benefits associated with being religious that are described within the Civil Registration Act.

In contrast, the Roman Catholic Church teaches discrimination against women (Catechism 1598) and that gay people are “intrinsically disordered” (Catechism 2358). This is described as positive belief, and so Roman Catholics may enjoy the benefits of being religious that are described by the Civil Registration Act. The creation of a separate category for parody is considered in detail below, but the central point here is that there are no objective criteria used to make these categorisations. The view of the Registrar General is that the language in the Civil Registration Act awards to the Civil Registration Service the power to decide what is and is not a religion, based purely on their personal opinions about whether any particular belief should be viewed positively or not.

Atheist Religions

The other reason stated by the Registrar General for refusing my application, was that an atheist cannot be religious. Specifically, the submission from the Registrar General states that:

“… in my view it is wholly contradictory to be both an adherent to a religious belief whilst being an atheist.”

Quote from the Registrar General of Ireland

The Irish Catholic Bishops have regularly carried out research into the beliefs of adherents to Catholicism in Ireland. Their report from the 2010 research is available at the bottom of this page. On page 12 of that document, it is stated that more than 10% of Irish Catholics do not believe in god, and are therefore atheists.

Moreover as I had stated in my written submission as part of the appeal process, prior to my application the Registrar General had in fact already accepted several atheist groups as religious bodies in Ireland. For example, the Dublin Buddhist Centre openly states on their website that they do not worship any god, thereby explicitly repudiating precisely the definition of a religious body that is contained within the Civil Registration Act. There are several other groups that are registered as religious bodies by the Registrar General too, despite the fact that they openly welcome atheist adherents. The Unitarians are one such group.

Importantly, in my written submission I suggested that the appeal process might allow for an oral hearing so that I could explain how my atheism is perfectly consistent with religiosity. Specifically, I wrote as follows:

“While I don’t believe that the content of my religious beliefs should be at issue with respect to my application, if you are interested I will be happy to provide a full explanation of those beliefs.”

Quote from my Legal Submission

Such an oral hearing would have allowed me to explain that not believing in a literal Flying Spaghetti Monster, does not imply that Pastafarians cannot meet the definition of a religious body; in the same way that not believing in a literal Yahweh, does not imply that Unitarian atheists cannot be members of a religious body.

Appeal Decision

The full text of the decision following consideration of my appeal is available at the bottom of this page. The decision initially appears to accept my arguments about atheist religions in stating as follows:

“While Mr Hamill correctly cites that there are many atheist religions across the world and he cites two in Ireland, the key issue for me as the Appeals Officer, is firstly, whether or not it is likely that Mr Hamill remains an atheist and secondly, is it reasonable for an atheist to believe in a deity such as the Flying Spaghetti Monster.”

Quote from Appeal Decision

That is, the appeal decision wrongly assumed that I must believe in a literal Flying Spaghetti Monster, even though my request for an oral hearing to explain my beliefs was rejected on the following basis:

“I don’t think much would be gained from conducting an oral hearing with the Appellant and I note that the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights’ General Comment No. 22: The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Art. 18), states that ‘no one can be compelled to reveal his thoughts or adherence to a religion or belief’.”

Quote from Appeal Decision

It is indeed a human rights abuse to compel someone to reveal their beliefs, if they wish to keep those beliefs private. However, this of course would not be relevant since I had already made it clear that I did not wish to keep my beliefs private, and that I was happy to discuss those details. A full copy of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights General Comment No. 22 on the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, is available at the bottom of this page. In addition to the quote from that document that was included within the appeal decision, it also states as follows:

“Article 18 protects theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs, as well as the right not to profess any religion or belief. The terms “belief” and “religion” are to be broadly construed. Article 18 is not limited in its application to traditional religions or to religions and beliefs with institutional characteristics or practices analogous to those of traditional religions. The Committee therefore views with concern any tendency to discriminate against any religion or belief for any reason, including the fact that they are newly established, or represent religious minorities that may be the subject of hostility on the part of a predominant religious community.”

Quote from High Commissioner for Human Rights

It is noteworthy that this document insists that religion must be “broadly construed” and cannot be limited to the “traditional religions” only, since the Registrar General has explicitly limited his interpretation of religion to the “recognised World religions”.

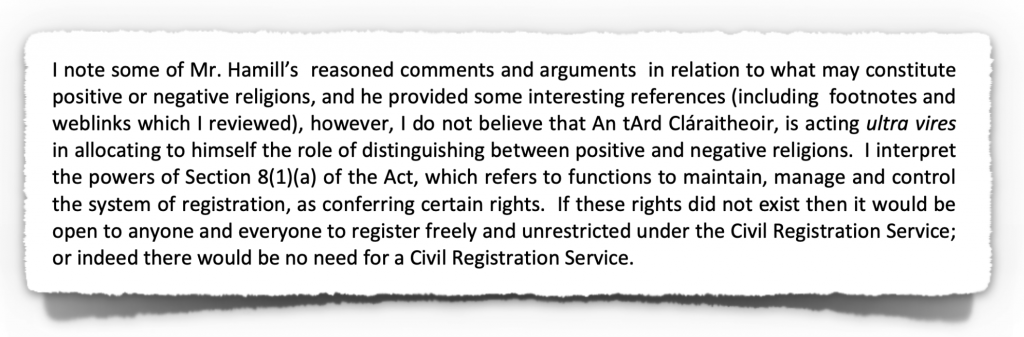

However, the central issue within the appeal was whether or not the definition of a religious body within the Civil Registration Act, allows the Registrar General to create categories of positive and negative beliefs, and then use purely subjective opinions to award civil benefits to some citizens and not others. The appeal found that the Civil Registration Act does implicitly confer this power on the Registrar General, and the relevant extract from the decision is illustrated below.

The logic here seems to be that if the Registrar General couldn’t deem some beliefs to be acceptable and others to be unacceptable, then all citizens in this Republic would be able to enjoy the same civil benefits as the religious. This is apparently an appalling vista, which must be avoided at all costs. The decision also goes on to refer repeatedly to some separate litigation that I engaged in under the Equal Status Act, in which the decision also sought to distinguish between religion and parody. The details of that case are provided below.

The Equal Status Act

Previous to my appeal under the terms of the Civil Registration Act, I had litigated a case of religious discrimination under the terms of the Equal Status Act. In this earlier case, I made the argument that a different Pastafarian denomination had suffered religious discrimination by Dublin City Council. The solicitor and barrister acting for Dublin City Council successfully argued that the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster is a parody, as it does not entail beliefs that are sufficiently serious. The full text of the decision is available at the bottom of this page and it is published as Adjudication Reference ADJ-00011817 and Complaint Reference CA-00016014-001.

There is no doubt that some Pastafarians within some denominations of the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, sometimes engage in parody. However, the same can be said for the adherents to all religions. For example, perhaps the most famous parody and satire about religion of all is the Lilliputian conflict between the Big-Endians and the Little-Endians. Gulliver’s Travels was authored by Jonathan Swift, who was the Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. It is perfectly clear then that it is entirely possible to be religious and also to engage in parody of religion. Religion and parody are not mutually exclusive categories. Instead, the question is whether Pastafarianism consists entirely of parody, or if there is some level of seriousness to these beliefs also.

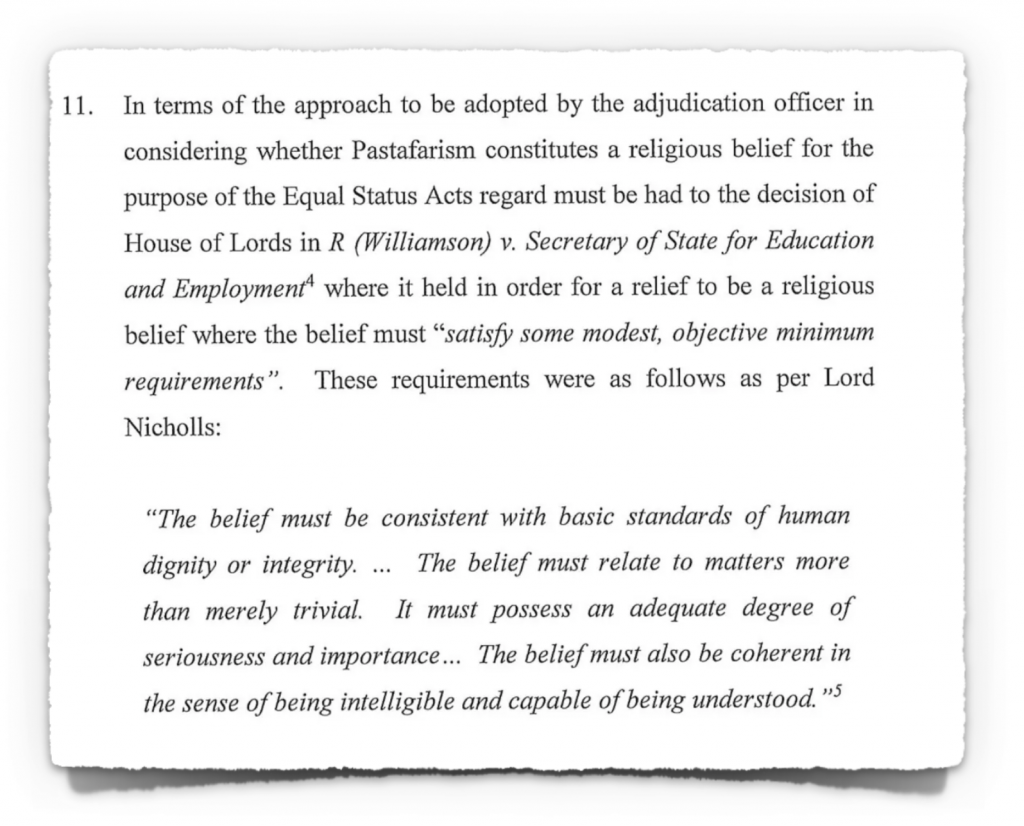

The full legal submission made by the barrister for Dublin City Council is available at the bottom of this page. Within this document, the legal test for what constitutes a religious belief is described in the extract illustrated below.

My legal submissions addressed directly how the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster meets this test, and full copies of all those legal submission documents are available at the bottom of this page. Those legal arguments refer to the Constitution of my Pastafarian Church, which states as follows:

“Members shall … recognise that there is no compulsion in religion and support a secular State for a pluralist people, such that the civil law should remain entirely neutral in matters of belief, allowing all people to practice their faith according to full respect for the human right to the freedom of religion.”

Quote from Pastafarian Constitution

That is, consistent with how the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster started during campaigns to prevent public schools teaching religiously inspired creationism in science classes, my Pastafarian denomination included a belief in secularism. The secular beliefs espoused, involved a commitment to the separation of Church and State, such that a State that remained neutral in matters relating to religion was preferred. Moreover, my legal submission went on to argue that as per the decision of the European Court of Human Rights in Lautsi v Italy, a belief in secularism possesses the adequate degree of seriousness in order to earn the relevant protections. A full copy of the European Court of Human Rights decision in that case is available at the bottom of this page, and §58 states as follows:

“Secondly, the Court emphasises that the supporters of secularism are able to lay claim to views attaining the “level of cogency, seriousness, cohesion and importance” required for them to be considered “convictions” within the meaning of Articles 9 of the Convention … More precisely, their views must be regarded as “philosophical convictions”, within the meaning of the second sentence of Article 2 of Protocol No. 1, given that they are worthy of “respect ‘in a democratic society’”, are not incompatible with human dignity and do not conflict with the fundamental right of the child to education …”

Quote from Lautsi v Italy

My legal submission went on to refer to the Overview of Case Law on Freedom of Religion that has been published by the European Court of Human Rights. A full copy of that document is available at the bottom of this page, and my legal submission emphasised §11, which states as follows:

“The Convention institutions do not have competence to define religion, but it must be interpreted non-restrictively. Religious beliefs cannot be limited to the “main” religions. The religion in question does have to be identifiable, though an applicant’s wish to describe his or her belief as a religion will be favourably regarded in the event of an unjustified interference by the State. There is hardly any case-law concerning the main religions because the tenets are known and the relations with the States are well established. However, the issue is more delicate regarding minority religions and new religious groups that are sometimes called “sects” at national level. According to the Court’s current case-law, all religious groups and their members enjoy equal protection under the Convention.”

Quote from European Court of Human Rights

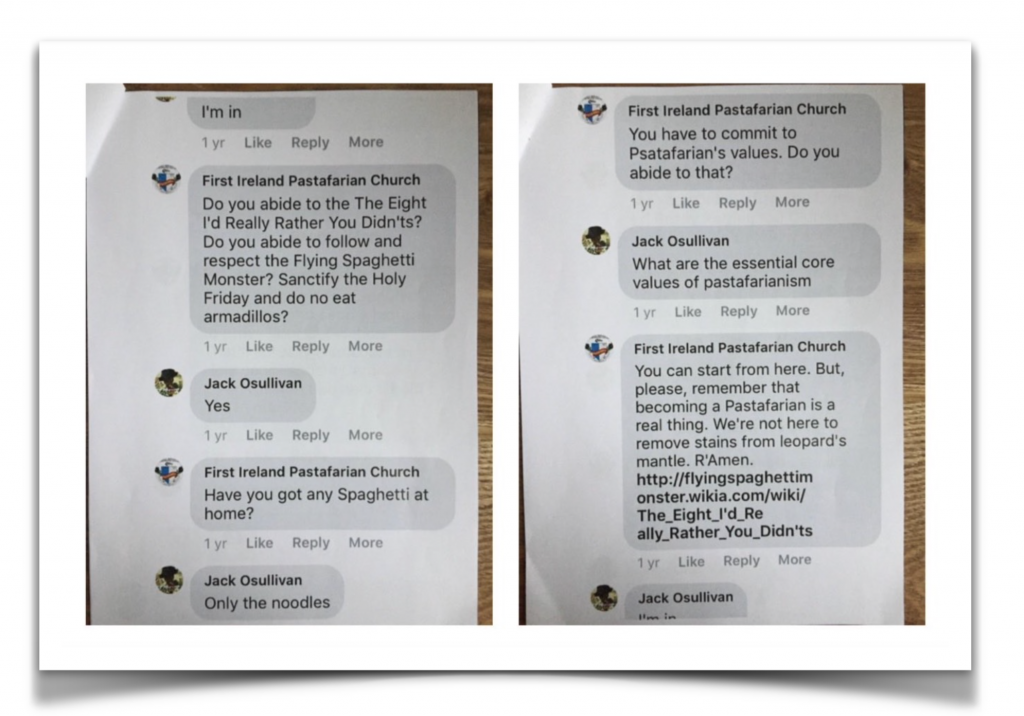

In the context of the commitment to secularism and other serious beliefs adhered to by my specific Pastafarian denomination, there was an onus on the legal representatives of Dublin City Council to adduce evidence demonstrating that all of these beliefs in fact lacked seriousness. An extract from the evidence presented at the hearing by the barrister acting for Dublin City Council, is illustrated below.

It seems that the solicitor acting for Dublin City Council may not have appreciated that there are many Pastafarians in Ireland, such that when messages from an Irish Pastafarian were discovered, it was assumed that they must have been written by me. The link in the messages illustrated is to a document that refers to a heaven containing beer fountains and strippers. However, I was able to inform the hearing that did not write any of this material, I have no idea who did write it, and I do not believe in a heaven that contains beer fountains and strippers.

The decision published following the hearing rejected this evidence, stating that it:

“… accepts the Complainant’s evidence that he is not associated with certain uncouth statements attributed to Pastafarianism”.

Quote from Decision in Equal Status Act case

However, since the Irish State had already recognised all kinds of fantastical supernatural beliefs as valid religions, there remained an onus to describe why my Pastafarian beliefs were not serious by comparison. The only single piece of evidence that the barrister acting for Dublin City Council was able to associate with me, was this tweet. When confronted with this evidence during the hearing, I accepted that this is indeed a photograph of me wearing a colander on my head while in the privacy of my own home.

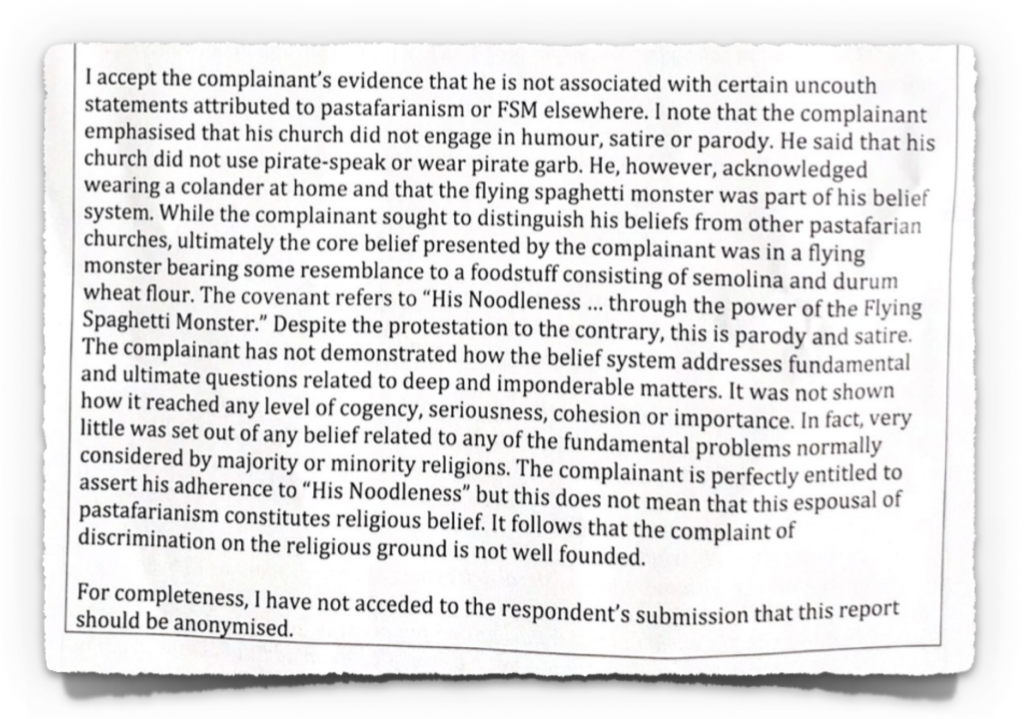

It was on the basis of this photographic evidence and the fact that I had “acknowledged wearing a colander at home” that the decision found against me. The concluding paragraph of the full decision is illustrated below, and refers to the offending millinery as the dispositive evidence.

One common feature of the decisions with respect to both the Civil Registration Act and the Equal Status Act, was arriving at the conclusion that Pastafarian beliefs fail to reach the required level of seriousness, while failing to make any effort to understand what those Pastafarian beliefs actually are. For example, §5.5 of my clarification submitted after the Equal Status Act hearing, stated as follows:

“In addition to a commitment to secularism, the Congregationalist Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster contains a deep set of other theological convictions, which inform a weighty and substantial aspect of the lives of its entire congregation. These theological beliefs include a range of serious, cogent, important and cohesive religious convictions. There is an open invitation to either the adjudicator, or to any member of Dublin City Council, to attend monthly worship with the Complainant in Dublin, in order to witness these aspects of the Complainant’s religion.”

Quote from my clarification after the Equal Status Act hearing

It is certainly the case that those who refuse to learn the serious and important aspects associated with any particular belief, will remain unaware that there are serious and important aspects to that belief. In this context, when the Irish State is asked what a religion is, the answer will merely be whatever any given civil servant happens to thinks it is (possibly after paying careful attention to the hats that adherents may wear in the privacy of their own homes).

Following this and other cases that I litigated under the terms of the Equal Status Act, I made a submission to Minister Roderic O’Gorman as part of his review of that legislation.

- 2019-08-12 Submission From Registrar General Of Ireland

- 2019-08-21 Submission Responding To Registrar General Of Ireland

- 2019-09-12 Decision On Appeal Of Registrar General of Ireland Rejection

- ECHR Manoussakis v Greece

- Religious Practice and Values in Ireland 2010

- General Comment No. 22 on the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion

- 2018-03-14 Legal Submission from Dublin City Council

- 2018-03-21 My Legal Submission in the Dublin City Council case

- 2018-03-22 My Clarification After the Hearing with Dublin City Council

- 2018-04-16 My Additional Submission In Response to Dublin City Council Evidence

- 2018-10-31 Full Decision in John Hamill vs Dublin City Council